Overview

•Notions of censorship and truth

•The indexical qualities of photography in rendering truth

•Photographic manipulation and the documentation of truth

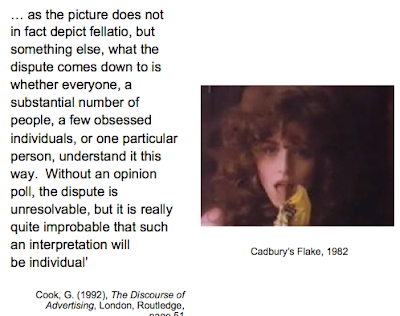

•Censorship in advertising

•Censorship in art and photography

Ansel Adams, Aspens

‘Five years before coming to power in the 1917 October revolution, the Soviets established the newspaper Pravda. For more than seven Decades,until the fall of Communism, Pravda, which Ironically means “truth”, served the Soviet Communist party by censoring and filtering the news presented to Russian and Eastern Europeans’

Aronson, E. and Pratkanis, A., 1992, Age of Propaganda: The Everyday Use and Abuse of Persuasion, New York, Henry Holt & Co., pages 269 - 270

Stalin with, and without, Tratsky

Easier to manipulate photos.

This is a manipulated photograph.

Kate Winslet on cover of GQ Magazine, with legs elongated in photoshop.

Very obvious that her legs have been elongated, is the representation of truth an important factor?

Can you manipulate real things to make it something different just to sell things.

Combine different things to change the message that is communicated.

‘At that time [World War II], I fervently believed just about everything I was exposed to in school and in the media. For example, I knew that all Germans were evil and that all Japanese were sneaky and treacherous, while all white Americans were clean-cut, honest,fair-minded, and trusting’

Elliot Aronson in Pratkanis and Aronson, (1992), Age ofPropaganda, p. xii

‘With

lively step, breasting the wind, clenching their rifles, they ran down the

slope covered with thick stubble. Suddenly their soaring was interrupted, a

bullet whistled - a fratricidal bullet - and their blood was drunk by their

native soil’ – caption accompanying the photograph in Vue

magazine

Tom

L. Beauchamp, Manipulative Advertising,

1984

Is this the exact moment of the death of this soldier, or was it just set up.

‘Whereas representation tries to absorb simulation by interpreting it as false representation, simulation envelops the whole edifice of representation as itself a simulacrum. These would be the successive phases of the image:

1.It is the reflection of a basic reality.

2.It masks and perverts a basic reality.

3.It masks the absence of a basic reality.

4.It bears no relation to any reality whatever : it is its own pure simulacrum.’

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations, 1981, in Poster, M. (ed.) (1988), Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings, Cambridge, Polity Press, page 173

‘In the first case, the image is a good appearance: the representation is of the order of the sacrament. In the second, it is an evil appearance: of the order of malefice. In the third, it plays at being an appearance: it is of the order of sorcery. In the fourth, it is no longer in the order of appearance at all, but of simulation’.

Jean Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations, 1981, in Poster, M. (ed.) (1988), Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings, Cambridge, Polity Press, page 173

‘As we approach the likelihood of a new Gulf War, I have an idea and it occurs to me that the Digital Journalist may be the place for it. As we all know, the military pool system created then was meant to be, and was, a major impediment for photojournalists in their quest to communicate the realities of war (This fact does not diminish the great efforts, courage, and many important images created by many of my colleagues who participated in these pools.). Aside from that, while you would have a very difficult time finding an editor of an American publication today that wouldn't condemn this pool system and its restrictions during the Gulf War, most publications and television entities more or less bought the program before the war began (this reality has been far less discussed than the critiques of the pools themselves)’

Peter Turnley, The Unseen Gulf War, December 2002, at http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0212/pt_intro.html

The "Mile of Death".

During the night of the 25th of February and the day of the 26th of February,

1991, Allied aircraft strafed and bombed a stretch of the Jahra

Highway. A large convoy of Iraqis were trying to make a haste retreat back to

Baghdad, as the Allied Forces retook Kuwait City. Many Iraqis were killed on

this highway. Estimates vary on the precise number of Iraqis killed during the

Gulf War. Very few images of Iraqi dead have been previously published

“It is a masquerade of Information: branded faces delivered over to the prostitution of the image”

Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did not Take Place, 1995, p.40

‘A carbonized Iraqi soldier, killed by Allied aircraft, as a convoy of Iraqi soldiers tried to retreat to Baghdad from Kuwait City at the end of the Gulf War. The scene of this photograph was on a highway that was to the northeast of Kuwait City’. Peter Turnley, 1991

‘A US Military graves detail buries the bodies of dead Iraqi soldiers killed along the Mile of Death, on the road between Kuwait City and Basra, north of Kuwait City’. Peter Turnley, 1991

‘A few days after the end of the Gulf ground war, an American soldier looks at a dead Iraqi soldier lying in the desert near where his convoy of vehicles was bombed and strafed by Allied aircraft as the convoy attempted to retreat from Kuwait back to Iraq. This was a different and much less exposed convoy that was bombed, from the Mile of Death. This convoy was on an obscure road to the north and east of Kuwait City. This attack left most of the Iraqi soldiers in the convoy carbonized and their bodies were buried by Allied Forces at the end of the war’. Peter Turnley, 1991

‘Most

of the reporting that reached American audience and the west in general

emanated from the Pentagon, hence severely lacking balance, as proven by the

total blackout on the magnitude of the devastation and death on the Iraqi side.

A quick statement of the number of dead (centered

around 100,000 thousands soldiers and 15,000 civilians) sufficed for

main-stream media audience. It is no wonder that this made-for-TV war started

at 6:30pm EST on January 16, 1991, coinciding with National News. Alas, much of

American audience today cannot distinguish between computer war games and real

war, between news and entertainment’.

‘Two intense images, two or perhaps three which all concern disfigured forms or costumes which correspond to the masquerade of this war: the CNN journalists with their gas masks in the Jerusalem studios; the drugged and beaten prisoners repenting on the screen of Iraqi TV; and perhaps that seabird covered in oil and pointing its blind eyes to the Gulf sky. It is a masquerade of information: branded faces delivered over to the prostitution of the image, the image of an unintelligible distress. No images of the field of battle, but images of masks, of blind or defeated faces, images of falsification. It is not war taking place over there but the Disfiguration of the world’

Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, 1995, in Poster, M. (ed.) (1988), Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings, Cambridge, Polity Press, page 241

‘While the publicity generated by such campaigns [Benetton] is immense – and their globalized distribution protects them from the effects of a ban in any one country – it is also surely shocking that the shock effect wears off so quickly. Perhaps the overall driving motive of such campaigns is in fact nothing new – but simply an astute loyalty to one of the oldest adages in the business: there is no such thing as bad Publicity’

Cook, G. (1992), The Discourse of Advertising, London, Routledge, page 229

“Decorative models do seem to increase recognition and recall of the advertisement itself. The same probably is true for nudity. Thus , as one article on that technique suggested, ‘While an illustration of a nude female may gain the interest and attention of a viewer, an advertisement depicting a nonsexual scene appears to be more effective in obtaining brand recall”’.

Phillips, M. J. (1997), Ethics and Manipulation in Advertising: Answering a Flawed Indictment, London, Quorum Books, page 121

Amy Adler – The Folly of Defining ‘Serious’ Art

- Professor of Law at New York University

- ‘an irreconcilable conflict between legal rules and artistic practice’

- The requirement that protected

artworks have ‘serious artistic value’ is the very thing contemporary art and

postmodernism itself attempt to defy

The Miller Test, 1973

- Whether ‘the average person, applying contemporary community standards’ would find that the work, taken as a whole, appeals to the prurient interest

- Whether the work depicts or describes, in a patently offensive way, sexual conduct

- Whether the work, taken as a whole,

lacks serious literary, artistic, political or scientific value

Obscenity Law

- ‘To protect art whilst prohibiting trash’

- ‘The dividing line between speech and non-speech’

- ‘The dividing line between prison and freedom’

Final Thoughts;

- Just how much should we believe the ‘truth’ represented in the media?

- And should we be protected from it?

- Is the manipulation of the truth fair game in a Capitalist, consumer society?

- Should art sit outside of censorship laws exercised in other disciplines?

- Who should be protected, artist,

viewer, or subject?

Further Reading;

Aronson, E. and Pratkanis, A., 1992, Age of Propaganda: The Everyday Use and Abuse of Persuasion, New York, Henry Holt & Co. Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations, 1981, in Poster, M. (ed.) (1988), Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings, Cambridge, Polity Press Jean Baudrillard, The Gulf War Did Not Take Place, 1995, in Poster, M. (ed.) (1988), Jean Baudrillard: Selected Writings, Cambridge, Polity Press Hawthorne C. and Szanto, A. (eds.) (2003) The New Gatekeepers: Emerging Challenges to free expression in the Arts, New York, Columbia University Arts Journalism Program

Naas M. (2010) The Truth in Photography, Edinburgh, Edinburgh University

Press